Antoni Taulé was born in 1945 and lives and works in Paris. Since his first show in Sabadell (1966) and later at the Maricel Palace in Sitges (1967), he has exhibited his work in museums, art centers, foundations and galleries all over the world, and his sets have appeared on all the top international stages.

Lux. In the instantaneousness of photography or in the slow delay of painting stretched out over time, Taulé waits and traps the moment when light emerges and penetrates interiors, defining their ample spaces. The places and the light are immobilized the minute they become symbolic and imaginary.

ROOM 1

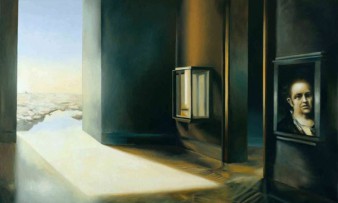

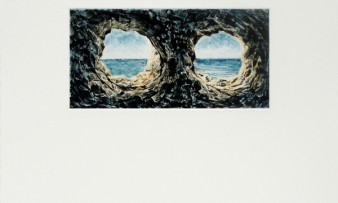

Why this attraction to large, empty spaces? The dialectic of emptiness exists in Taulé’s work: a dialogue of large, interior spaces with light (or with backlighting, like in the series of the caves he painted in Formentera, during the eighties, but also in pieces from other periods). A dialectic, by extension, between the space inside and the space outside, that permeates the painting through the almost cinematic projection of light. A light that reveals the dark interior and displays its disturbing and enigmatic nature. And at the same time it reminds us of the exterior landscape, indefinite, incommensurable. In Épouser les formes du monde (Marrying the shapes of the world, 2007), the light that pours in from outside onto the character contrasts with the Magritte-esque tone of the lamps on the walls that are hidden from the light coming in. So the interior is the stage for the light from outside. A luxurious stage, markedly architectural. And empty, but inhabitable in dreams. Because all of these spaces, these inexplicable situations, are made of the stuff of dreams. But exceptionally, there are some paintings that contradict this law: In Marée basse (Low Tide, 2005), Lætitia is in a solar landscape, in the middle of the receding water. Lætitia, Taulé’s first wife, would die that same year. Importance, likewise, of corridors, of doorways, of transient places, which are unpredictable spaces (Casa Taulé, 2016; Hotel Chelsea, 2016).

In paintings like L’Énigme (2016), that contains a perspective vision of parallel doors inside Villa Arconati (Milan), the metapictorial theme: the presence of a painting –that can be a painting by Taulé himself, as is the case here, or a pictorial quotation, like in L’Ange noir (2009)– institutes a kind of resonance, a kind of hyper-pictoriality. As if all previous and universal painting converged in this enigmatic call for light.

ROOM 2

MOMENTS, PRESENCES

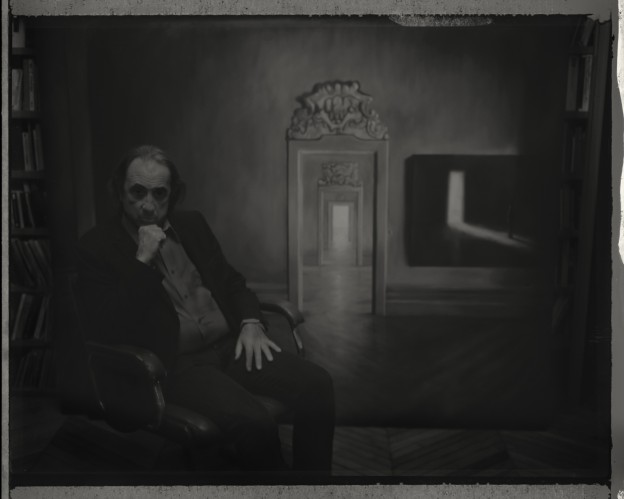

From the very start, in Taulé’s work, photographs were a means, a tool in the painting process. But as of a certain moment, the means got mixed up with the objective. The photographs were as enigmatic as the paintings. The places had to be empty, and above all it was necessary to choose the time and the day: it was very important to know how to capture the instant the sun was rising and the light permeated the interior.

Compared with painting, photography designates waiting for the moment, and after the moment itself, an instant; on the other hand, painting is spread out over its duration and is constructed progressively, in a series of brushstrokes and layers that transform the subject and impregnate it with an almost obsessive insistence. Since the seventies, in photographs like Bonnet rouge (Red Cap, 1977), Une histoire (A Story, 1978), and later, with Miroir (Mirror, 1985), Taulé’s camera captures the place’s disturbing strangeness, it lays out certain elements, people or objects, profoundly ambivalent, enigmatic, that can metamorphose later in paintings. If in photography the light, the main protagonist, clearly delimits the outlines of the places and objects, in paintings, the place and the light become symbolic, imaginary. The painter’s technique, softening and contrasting the subject, sometimes altering the perception of the place or the composition, and especially rethinking the place and the effect of the light, allows for passing into the full symbolic dimension. The characters are presences, as in Le grand chemin (The Highroad, 2015) or apparitions (Charlotte Roussel, 2016).

ROOM 3

The Stämpfli Foundation’s collection of art works brings together very wide-ranging forms of expression and trends emerging from Europe starting in 1960.

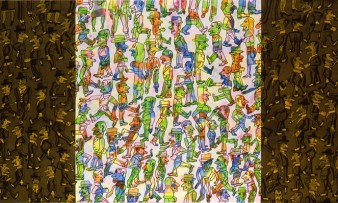

On display in this room is a selection from its permanent collection allowing us to see some of the different channels through which the young 60’s artists left behind the artistic concerns of previous generations, especially the abstraction of the immediate post-war period and the decade of the 50s.

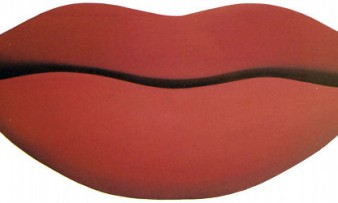

The overcoming of the traditional opposition between figurative art and abstract art is remarkable. A paradigm of this dissolution of boundaries between figurative and abstract art is Peter Stämpfli’s work. Enlarging the geometric pattern of automobile tires, he constructs volumetric shapes that lose their figurative origin and venture into the territory of geometric abstraction.

Actually, the art that takes its first steps these years placed the primary focus on a theoretic and practical revamping of the artistic act.

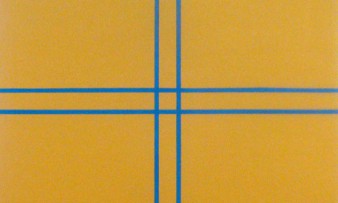

To this end, new languages are explored like monochrome, repetition, the search for rhythm through contrast or the reduction of painting to elemental and minimal symbols. Some examples are the works on display by François Arnal, Gérard Titus-Carmel, Olivier Mosset and Niele Toroni.

Jean-Michel Meurice and Daniel Dezeuze were part of the Support/Surface movement, characterized by attaching the same importance to materials and creative gestures as to the finished work.

Mark Brusse is a versatile artist. His work has moved on a number of different fronts. On the one hand, the creation of “sculptures” based on fitting together salvaged wood with other diverse materials that he’s collected, guided by chance. And on the other, participation with members of the group Fluxus in actions of short-lived creation or large installations adapted to specific spaces.

Jean Le Gac’s work is based on his own history and life as the protagonist of his work, developing an autobiography that blends reality and fiction and where he explains, defines, reflects on and questions the artist’s life.

Completing this room are the works by Pierre Tilman, poet-artist of elemental shapes, of letters and of color; and the Argentinean artist Horacio García-Rossi, an important exponent of lumino-kinetic art.

Additionally, Spanish Rafael Canogar is one of the ultimate representatives of the abstract informalism born in the 50’s and that was crystallized with the creation of El Paso, the most prominent group in the definition of the Spanish vanguard of that decade.